A comprehensive guide to diabetes for first aiders

Diabetes is a very common condition worldwide. It is estimated 29.1 million Americans (nearly 10% of the population) have diabetes. In this first aid blog post we discuss diabetes and consider the difference between type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

What is diabetes?

Diabetes Mellitus is a condition in which the amount of glucose (sugar) in the blood is too high because the body does not produce sufficient insulin. Insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas, helps glucose enter the cells where it is used as fuel by the body.

A lack of insulin means that glucose absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract can not be metabolised or stored and so reaches higher than normal levels in the bloodstream.

There are two main types of diabetes: Type 1 & Type 2.

Type 1 diabetes develops if the body is unable to produce any insulin. This type of diabetes usually appears before the age of 40. It is treated by insulin injections and diet and regular exercise is recommended.

Type 2 diabetes develops when the body can still make some insulin, but not enough, or when the insulin produced does not work properly (known as insulin resistance).This type of diabetes usually appears in people over the age of 40, although it can appear before the age of 40 in South Asian and African- Caribbean people or those with other risk factors. It is treated by diet and exercise alone or by diet, exercise and tablet or by diet, exercise and insulin injections.

The main aim of treatment of both types of diabetes is to achieve blood glucose and blood pressure levels as near to normal as possible. This, together with a healthy lifestyle, will help to improve well being and protect against long-term damage to the eyes, kidneys, nerves, heart and major arteries.

What are the complications of diabetes?

There are several complications of diabetes. These are:

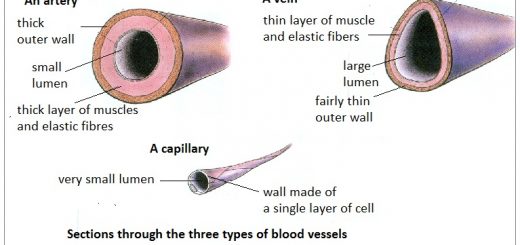

- cardiovascular disease due to the build up of atheroma (fatty substances) and calcification (mineral salts) in arteries;

- susceptible to infections;

- renal failure due to vascular changes and infection;

- hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar); and

- hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar).

Hypoglycaemia occurs when insulin is in excess of that needed to balance the patient’s food intake and energy expenditure. If untreated it will lead to unconsciousness and if prolonged, irreversible damage can occur.

Hypoglycaemic patients may appear drunk although alcohol may also induce hypoglycaemia. You should never discount the possibility that a patient who appears to be drunk may in fact be hypoglycaemic. Most intoxicated (drunk) patients will have their blood glucose levels recorded at hospital to ensure that they are not hypoglycaemic.

Most diabetics have blood glucose meters for recording their glucose levels at home. If you are not authorised to take a blood glucose reading ask if the patient, their family or carer, is able to take a blood glucose reading. This will assist you in determing the cause of the medical emergency and identify possible treatment regimes.

Co-operative and conscious hypoglycaemic patients can be given oral glucose (lucozade, milk with sugar or Hypostop gel) until sugar levels improve.

Unconscious, uncooperative patients, or those without a gag reflex, should not be given any oral glucose, their ABCs ensured and transported to hospital. Where possible, request the presence of an ambulance from the statutory services to administer glucagon (a drug which mobilises glucose stored in the liver) and intravenous glucose (glucose injected into a vein).

Hyperglycaemia is often the presenting feature of diabetes. Patients who have not been diagnosed as diabetics will often go to their doctor complaining of excessive hunger, thirst and urination. On testing their blood glucose levels they are often found to be high.

Diabetic patients who are hyperglycaemic have often been ill for some hours or days and have since deteriorated − most calls for assistance are made when the patient falls unconscious. Treatment is to ensure the patient is safe and call an ambulance.

Assessing a diabetic patient

When obtaining a history from a diabetic patient, or their family, the following points are useful to record:

- what happened?

- is the patient diabetic?

- is the patient on insulin, tablets or controlled by diet?

- when did the patient take their last insulin injection or tablets?

- is the patient’s diabetes usually well con- trolled?

- has this happened before?

- has the patient eaten?

- has the patient undertaken an unusual amount of exercise or activity?

- has the patient being taking medication as prescribed?

If, despite obtaining a full assessment and history, you are unable to determine whether the patient is hypoglycaemic or hyperglycaemic, and they are conscious with a gag reflex give oral glucose.This will make very little difference if the patient is not suffering from hypoglycaemia, but will improve the blood glucose level and lessen the risk of brain injury if they are.

Hypoglycaemia vs Hyperglycaemia

It is important for first aiders to know the difference between high and low blood sugar.

|

Assessment |

Hypoglycaemia |

Hyperglycaemia |

|

History Onset Blood glucose level Signs and symp- toms |

Too much insulin. Little or no food. Unexpected exercise. Gastrointestinal disturbances. Usually rapid with ‘good health’ previously. Usually less than 3 mmol/l Pale, cold, clammy skin. Bounding, rapid pulse. Normal or high blood pressure. Normal or shallow breathing. Dizziness. |

Omission or insufficient insulin. Usually slow with ill health a few days before. Usually greater than 20 mmol/l Flushed, hot, dry skin. Weak, rapid pulse. Polydipsia (excessive thirst). Polyuria (excessive urine output). Restless, drowsy or lethargic behaviour. |