First aid for head and skull injuries

Head injury is the most common cause of death in trauma. Death can either be the result of an isolated head injury or due to other traumatic injuries. Although the incidence of head injury is high, the incidence of death from head injury is low (6-10 per 100,000 population per annum).

Head injury is the most common cause of death in trauma. Death can either be the result of an isolated head injury or due to other traumatic injuries. Although the incidence of head injury is high, the incidence of death from head injury is low (6-10 per 100,000 population per annum).

70 – 88% of all people that sustain a head injury are male, 10-19 per cent are aged 65 years or over and 40-50% are children. Falls (22-43%) and assaults (30-50%) are the most common cause of a minor head injury, followed by road traffic collisions (approximately 25%). Alcohol may be involved in up to 65 per cent of adult head injuries.

Brain injury can be divided into two categories:

• primary brain injury: direct trauma to the brain and associated vascular injuries sustained as a direct result from the initial collision

• secondary brain injury: neurological damage after the initial impact.

While there is little that can be done for the primary brain injury, protecting the airway and ensuring sufficient breathing and circulation can reduce the effect of secondary damage.

The initial care of the head-injured patient is to establish an airway and administer oxygen (if trained). A common symptom of traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a loss of consciousness, resulting in a risk to the airway.

As with all trauma, it is essential to understand the mechanism of injury involved in the event; when dealing with patients with head injuries also consider the possibility of a cervical spine (neck) injury.

The presence of a ‘bull’s-eye’ to the vehicle windscreen, especially if hair is stuck to the glass, suggests an impact with the patient’s head.

Bystanders are important as they will be able to inform of any changes in the level of consciousness, history of memory loss – both before and after the injury – and an inability to move limbs, all vital prices of information.

A patient who was initially unconscious, subsequently regained consciousness and then becomes increasingly drowsy or aggressive could have a cerebral bleed.

As always, the primary survey addresses the patient’s airway, breathing, circulation and disability.

Significant head injury can alter breathing patterns. In patients with a reduced level of consciousness the tongue may be blocking the airway, as could bleeding and swelling from facial trauma.

First aiders should also assess:

- pupil response and level of consciousness

- evidence of brain matter coming from a wound, indicating a compressed skull fracture

- evidence of blood or cerebrospinal fluid from the nose, mouth or ears;

- evidence of scalp and facial trauma, especially those suggesting underlying fractures. Battle signs (bruising behind the ear) and periorbital bruising (bruising around the eyes) may indicate a fracture to the base of the skull.

- for the presence of associated spinal cord injury, this should be assumed in all but the most minor of head injuries.

- sensory and motor function in all four limbs

- consider the relevance of the patient’s own medication, for example, a patient on anti-coagulant (blood thinning) therapy is at higher risk of developing intracranial bleeding (bleeding within the skull).

Evaluate if the patient is demonstrating any time critical features, for example any problems with ABC, if so immobilise and transport or arrange rapid removal to a suitable hospital.

In non-time critical patients a more detailed secondary survey can be performed. The initial aims of managing head injuries is to:

- deliver sufficient oxygen to the brain

- minimise cervical spine injury

- obtain the baseline observations and history

The airway should be managed through the use of the jaw thrust (head tilt chin lift may cause damage to the cervical spine and hence should not be used) and suction. Airway adjuncts, depending on levels of training, should be used and further medical resources called for.

Patients who have sustained a head injury and present with any of the following risk factors should have full cervical spine immobilisation attempted unless other factors prevent this:

- reduced level of consciousness at any time since the injury;

- neck pain or tenderness;

- any neurological deficit;

- any paraesthesia (abnormal sensations) in the limbs

- any other clinical suspicion of cervical spine injury.

Cervical spine immobilisation should be maintained until full risk assessment indicates it is safe to remove the immobilisation device.

All patients with serious head injuries should receive supplemental oxygen (if trained) as hypoxia can worsen head injuries.

A mini-neurological examination of the patient will form part of the baseline against which any improvement or deterioration in the patient can be recorded. This examination should consist of:

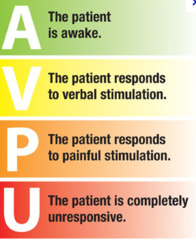

- Assessment of conscious level. This is the most sensitive indication of changes in the patient’s condition. While AVPU is easier to use (and should be used for the initial

primary survey) the Glasgow Coma Scale is more sensitive to changes in the conscious level. While the sum of the three components can be added to give the Glasgow Coma Score (i.e. GCS of 13) it is better to describe the response in words, for example ‘eyes: open to voice, verbal: confused conversation, motor: withdraws from pain.’ This avoids having to remember the numbers assigned to each response and provides a clearer picture on hand over.

- Pupil response. Pupils should be round, equal in size and both should constrict equally if a light is shone into one eye. All abnormalities should be noted. Unequal pupils are caused by pressure being exerted on the nerves travelling to and from the eyes. For pressure to be exerted on these nerves the patient is unlikely to be conscious due to the increased intracranial pressure.

- Motor response. If the patient is obeying commands, compare the muscle power between both sides and between each limb. In the unresponsive or uncooperative patient, spontaneous movement should be noted and the reaction to painful stimuli compared between the two sides. Seizures are quite common following a major head injury. It is important to differentiate between a convulsion occurring within seconds of the impact which is of little significance and a convulsion which follows after a longer interval which may indicate post traumatic epilepsy, hypoxia or hypoglycaemia.

The severity of head injuries may not be immediately apparent, therefore the first aider must consider the mechanism of injury and perform regular evaluations of the patient. Immediate pre-hospital management is protecting the airway, ensuring sufficient oxygenation to prevent hypoxia and treating other possible injuries.

primary survey) the

primary survey) the