Managing Food Poisoning in Children

Food poisoning, a type of gastroenteritis (digestive tract inflammation) caused by eating contaminated food, results in severe abdominal cramps, repeated vomiting, diarrhea and muscle weakness. These symptoms develop suddenly between three and 24 hours after the food is consumed.

Some types of food poisoning are quite dangerous, especially to infants and small children. Fortunately, proper handling and storage of food can usually prevent the problem.

What Causes Food Poisoning?

Food poisoning is generally caused by bacteria allowed to multiply in improperly refrigerated or stored food. Some microbes, such as Staphylococcus, release toxins that inflame the stomach, causing nausea and vomiting. Salmonella bacteria (commonly found in raw eggs and shellfish, and responsible for many cases of food poisoning) act directly on the intestinal lining, causing painful cramping. Shigella, another food-borne microbe, is responsible for severe diarrhea (dysentery).

In babies, food poisoning is often caused by E. coli bacteria, which are passed from contaminated fluids in bottles. Botulism, a potentially deadly form of food poisoning that leads to paralysis, is caused by a toxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum in cans that have not been sealed properly.

Another form of botulism known as infant botulism is caused by bacterial spores sometimes found in honey. If the baby eats infected honey, the organism may produce toxins in the digestive tract. This type of botulism produces constipation, hunger, thirst, listlessness, loss of muscle tone and inability to suck in children under a year of age. In severe cases, the respiratory muscles of the chest become paralyzed, requiring artificial respiration until recovery.

It can be hard to distinguish food poisoning from viral gastroenteritis. The symptoms of food poisoning may come on more suddenly, however, and other members of the household (or classmates) who ate the same food also will be affected.

Seeking Medical Attention

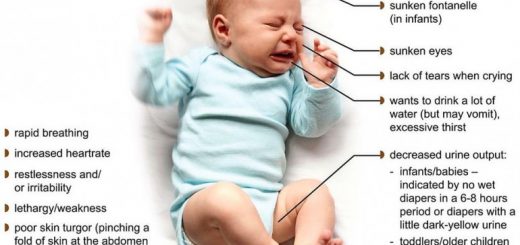

Always seek medical advice for a child with food poisoning. The younger the child, the greater the risks of complications such as dehydration. A baby who has been vomiting and had diarrhea for six hours or longer should be taken to an emergency room. With an older child, you can wait a little longer to see if symptoms abate, but if they do not improve within 24 hours, see a doctor.

Treatment of Food Poisoning

Hospitalization may be necessary to administer intravenous fluids until the body had rid itself of the poison. Both forms of botulism can be treated by administration of an antitoxin that neutralizes the bacterial toxin responsible for the symptoms.

Preventing Food Poisoning

- Discard all food that has been improperly prepared or stored, even if it does not look or smell bad

- Don’t assume that a thorough reheating will kill all bacteria in improperly stored food. Staphylococcus bacteria, for example, releases a toxin that is resistant to heat.

- Refrigerate leftovers before they cool down. If food is cooled or reheated slowly, salmonella can reproduce.

- Hot mayonnaise is a notorious breeding ground for bacteria. It’s best to leave mayonnaise-based salads out of the picnic basket on hot summer days.

- Leave foods that could spoil out of your child’s lunch box.

- Never give honey to an infant under a year old.

Looking After a Child With Food Poisoning

For one to six-year-olds:

- Be certain that a child recovering from food poisoning gets plenty of rest.

- Follow the doctor’s instructions for replacing fluids lost through diarrhea and vomiting. Many doctors recommend solutions such as Pedialyte.

- Withhold food until the doctor instructs you to resume feedings.

- Reintroduce other fluids gradually, starting with clear soup, tea, gelatin and flat soda. Avoid milk for a while.

- Proceed to rice cereal and potatoes after a day or two of the clear diet.

- Let the child resume a normal diet in about three days.

For infants:

- Continue breast feeding (if you normally do so), but cut out formula feedings and solid feedings for as long as the doctor recommends. Infants are more likely than older children to need hospitalization and intravenous feedings.